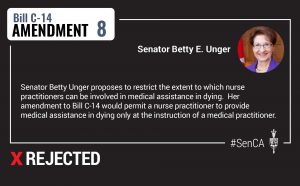

Honourable senators, I rise today to move an amendment to Bill C 14 regarding the role of nurse practitioners.

Honourable senators, I rise today to move an amendment to Bill C 14 regarding the role of nurse practitioners.

Doctors and nurses have worked in a collaborative relationship for generations, but by virtue of their advanced education, doctors have been in charge.

My amendment is straightforward; it seeks to affirm the continuation of this symbiotic relationship. To be clear, my amendment does not prohibit nurse practitioners from being involved in the process. It simply makes certain that they do so under the guidance and instruction of a physician, as is the practice in many provinces and was recommended by the Special Joint Committee on Physician Assisted Dying.

Furthermore, this amendment does not permit nurse practitioners to assess patients for competency, which must be done only by a qualified physician.

I believe this change will be appreciated by registered nurses who are entitled to practice as nurse practitioners. The amendment appears lengthy, only because it impacts the legislation in 21 different places due to the frequency in which the words “nurse practitioner” appears in the bill. It makes changes to pages 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11. However, the office of the law clerk advises me that, nonetheless, it is only one amendment and only the length of my reading makes it appear complicated.

I recognize that, for some senators, your first impulse will be to oppose this amendment, but I appeal to you to consider what I have to say. This issue has been characterized as one of access.

The Minister of Justice, when speaking to the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, said it this way:

“In terms of nurse practitioners, Minister Philpott and I… recognized the need to ensure access to medical assistance in dying across the country and that… more remote areas communities sometimes don’t have the benefit of a doctor… “

The minister’s concern is that if we do not allow nurse practitioners to provide medical assistance in dying, then access will be restricted. In fact, the only rationale provided for granting this role to nurse practitioners is to ensure access.

In response to this, I will say two things. The fact is, we don’t know how many people will ever request medical assistance in dying. Thus, this would be providing a solution to a problem that may not exist. The number of requests, due to the size of these communities, is likely to be very small and infrequent and I’m speaking about communities in the North. Therefore, I’m surprised that this aspect of the legislation is so overbroad in comparison to what the reality is likely to be. If there is a request, surely the solution is not to provide a sweeping exemption to nurse practitioners who have less training than a physician.

I would propose a better solution is to follow the process already utilized in health care. When a medical service is not available at a particular facility, either a doctor who specializes in that treatment is brought in or the patient is transferred to a different facility.

Consider what Carolyn Pullen, Director of Policy, Advocacy and Strategy with the Canadian Nurses Association said to the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs:

“In both the case of abortion and in medical assistance in dying, these are not emergency situations. There is time, even in remote or rural circumstances, where if a provider needs to recuse themselves from the process, there would be policies and practices in place to bring in a substitute provider to provide that care.”

Now, Ms. Pullen was actually speaking to a question on conscientious objection. However, her response provides evidence applicable to assisted dying as well.

My second point, colleagues, is with respect to adequate safeguards. Nurse practitioners provide significant and valuable services in health care. But as I previously stated, they do not have the training that a physician does, and there is broad acceptance that more critical procedures should be left to those who are best qualified. We expect this as a safeguard not only in health care but especially in end of life care, because nurses will have never received training in that discipline; yet the aspect of Bill C 14 that grants nurse practitioners the same duties as physicians increases access at the expense of safeguards.

Colleagues, consider this: Aside from abortion, there is no practice in health care more deadly than the one we are legislating on, yet we’re being asked to accept that someone who does not have the training and experience of a physician should be able to assess and approve a patient for competency and consent.

Furthermore, and this is no small thing, they could then carry out the act of ending that patient’s life, which has never before been part of their nursing culture or experience. We are the last bastion before Canada enacts legislation for physician hastened death.

Honourable senators, the Supreme Court was clear that a system of medical assistance in dying would require stringent and well enforced safeguards. Without this amendment, we will fail to comply with this directive.

I recognize that some senators may have concerns about jurisdictional issues, so allow me to speak to this briefly. I have considered this issue of jurisdiction, and while I acknowledge that we must be cognizant of jurisdictional issues, I believe we would be making a mistake to defeat this amendment on that basis.

Allow me to explain. This bill is a federal bill which contains explicit permission granting nurse practitioners to carry out medical assistance in dying. I am simply recommending that this permission be contingent on the instruction of a physician.

Because we are amending the Criminal Code of Canada to make an exemption with respect to homicide, it is entirely appropriate for Parliament to provide clear direction regarding who has the right to approve and to administer such a practice. I believe this is a necessary amendment, and I am asking for your support today.